In Nietzsche's posthumously published notebooks (aka The Will to Power), one of his entries from 1888 reads thus:

For a philosopher to say, 'The good and the beautiful are one,' is infamy; if he goes on to add, 'also the true,' one ought to thrash him. Truth is ugly. We possess art lest we perish from truth." (Will to Power; Section 822)This entry not only mocks the idea of a Platonic unity of the good, true and beautiful, it pits truth and beauty against one another. The possibility of such a conflict reflects a theme that preoccupied Nietzsche from his early writings on art in The Birth of Tragedy all the way through middle works (e.g. The Gay Science) to the late works (e.g. Beyond Good and Evil). Unlike many philosophers who are concerned with the conditions under which a statement might count as being true, Nietzsche asks why philosophers, theologians and scientists exhibit such a strong "Will to Truth"-- i.e. why they hold the value of truth for its own sake to have a status overriding that of all other categories, especially those which are aesthetic and artistic in nature. (Note: There's a post on N's notion of the "Will to Truth" which I posted here this week). He is not necessarily rejecting a place for putative truths or facts in philosophy, science and everyday life. Rather, he is pointing out that what he calls the "intellectual conscience," which posits obligatory truth-telling (ala Kant) and the acquisition of truth as the summom bonum, fails to grasp the power of "untruth"; the realm of imaginaries we find in visual arts, works of fiction, music etc. The cognitive (knowledge-seeking) and aesthetic perspectives often conflict, and it is far from clear that in each and every case of conflict the value of truth is greater (meaning, for Nietzsche, more conducive to vitality and health) than the value of the aesthetic. Nietzsche holds that:

a) Artworks and aesthetic experience can be as vital to human well-being as truth (or more).

b) Living should be understood, in large part, as a work of art in progress. In The Gay Science ( 299),

Nietzsche asks, " [H]ow can we make things beautiful, attractive, desirable for us when they are not?" He answers the question a few lines down stating that, "we want to be poets of our lives, first of all in the smallest, most everyday matters." (GS: 299). Nietzsche describes this mode of living as "self-creation;" as the ongoing process of "giving style to one's character" (GS:290)

Again, in The Gay Science (section 107), under the heading "Our ultimate gratitude to art" - Nietzsche writes,

"As an aesthetic experience, life is still bearable for us."He is echoing his earlier Birth of Tragedy in which he wrote,

"It is only as an aesthetic phenomenon that existence and the world are eternally justified."(BT:5)Translator and philosopher, Walter Kaufmann suggests that Nietzsche, in The Gay Science (10 years after Birth of Tragedy) is reminding the reader that it was in that earlier book that he first drew attention to the problematic relationship between science (as the "Apollonian" quest for truth) and art (as the "Dionysian" quest for beauty and deep aesthetic fulfillment). In The Gay Science, Nietzsche elaborates on the theme first taken up in Birth of Tragedy, and counsels us to "discover the hero no less than the fool in our passion for knowledge; we must find pleasure in our folly or we cannot continue to find pleasure in our wisdom." (GS 107) In this passage he seems to strike a balance between the ideals of aesthetic experienced (however much it may stray from true accounts of the world) and the truth (conceived as that which which is taken to be the case--i.e. factuality). If there is something heroic about the tireless search for truth and knowledge, there is also something foolish about such a quest undertaken with the naive assumption that truth is the royal road to well-being. For example, war and killing are horrendous and damnable brute factsof life, but even the the rage of Achilles in The Iliad is something that readers of Homer through the centuries have long understood as beautiful and life-enriching poetry.Even the clever, intentional lying of Odysseus charms and pleases the goddess Athena in Homer's Odyssey, though the "intellectual conscience" of modern philosophers and scientists cannot celebrate trickery and dishonesty as the Greek goddess does. Art has the power to enrich human experience, but very often it does so by providing us with fulfilling illusions and flights of fancy that create worlds rather than reporting on them. This disjuncture of art and truth reveals, thinks Nietzsche, that the aesthetic perspective has great value despite its being at odds, in many cases, with the will to truth and putative facts associated with it. Ultimately, Nietzsche is pointing to the limits of rational inquiry as a means of deriving a sense of meaning and joy from life. It is fine to a point-- and Nietzsche was excited by Darwin's theory of evolution and the spirit of experimentalism associated with it. But we should be able, at times, to rise above our moral commitment to "irritable honesty" (unconditional truth-telling and fidelity to facts). He writes:

Precisely because we are, at bottom, grave and serious human beings-- really more weights than human beings-- nothing does us as much good as a fool's cap: we need it in relation to ourselves. We need all exuberant, floating, dancing, mocking, childish, and blissful art lest we lose the freedom above things [levity, "lightness of being"] that our ideal demands of us...We should be able to stand above morality, and not only stand with the anxious stiffness of a man who is afraid of slipping and falling any moment, but also to float above it-- play. How then could we possibly dispense with art-- and with the fool? And as long as you are in any way ashamed before yourselves, you do not yet belong with us. (GS Section 107)Nietzsche valued the ability to laugh at oneself, to see and enjoy seeing that which is foolish rather than succumbing to the "stiffness" of the serious, pious, and principled stance of truth-worship. The truth may not set you free. Reason may not lead to beneficial insight. Even that which transgresses reason, that which is not rational,is too often thought of in terms of theophany, epiphany, or the "eureka" of the scientific genius -- all serious, "weighty" stuff. Nietzsche saw that the search for Truth (first in religion and later science), too easily gives way to a restrictive notion of living a life of "principle"-- i.e. a life aimed at The "Good-in-itself." He points instead to a Heraclitian appreciation of life; one where we can say with that enigmatic early Greek philosopher, "Time is a game of draughts played by a child."

By contrast, too many of us are "serious" and consider such a perspective to be--well-- "childish." Instead we pursue truth with a nagging and "irritable" conscience, telling ourselves we SHOULD or even MUST seek and honor truth, because it is honest, virtuous and leads to that which is all-important: The Ultimate Truth (a metaphysical fiction that goes beyond reliable factual descriptions, positing a transcendent reality-- be it God or absolute knowledge in science). In Thus Spake Zarathustra, Nietzsche depicts conscience as a dragon that the "free spirits" among us would slay. He calls the monster the "Tyranny of the Should." I once saw this metaphor used in a book on psychotherapy. "Don't 'should' on yourself," the author advised. As with other famous Nietzsche paraphrases there is at best a partial understanding in the popular interpretations, but enough so --perhaps-- to make his way of thinking seem less alien than at first it might appear to be. For the inability to laugh at ourselves , thinks Nietzsche, is not only based on vanity and self-importance, but it also impoverishes and stultifies our lives. The solemn or overly-serious attitude tends to thwart creativity, joy and playfulness associated not only with art but the enjoyment of life. Of course, art is, in a sense, serious. It requires devotion, discipline and rationality in order to be executed at all. But if it is serious, we might say that it is also "serious fun" or, in Nietzsche's idiom, "profound joy." There is a sense in which even a disturbing novel or movie about loss and grief can elevate us from our mundane concerns so that we "float above" the mundane for a while. This doesn't mean there is nothing to be learned from the film or book or what-have-you. But ultimately, for Nietzsche, the function of art is not didactic. We turn to art in large part to replenish our hearts and minds with the unashamed innocence of the fool, who without being inhibited by norms and "shoulds" at every turn,

is at least free to experience and express life afresh.

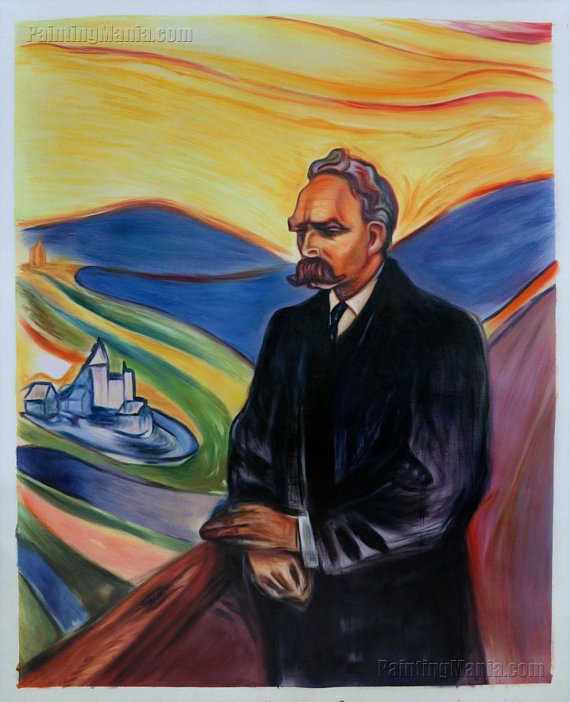

Portrait of Nietzsche by Edvard Munch, 1906Q.How important is the non-rational realm of "play" to you? How important is the quest for truth? Are they compatible?

No comments:

Post a Comment